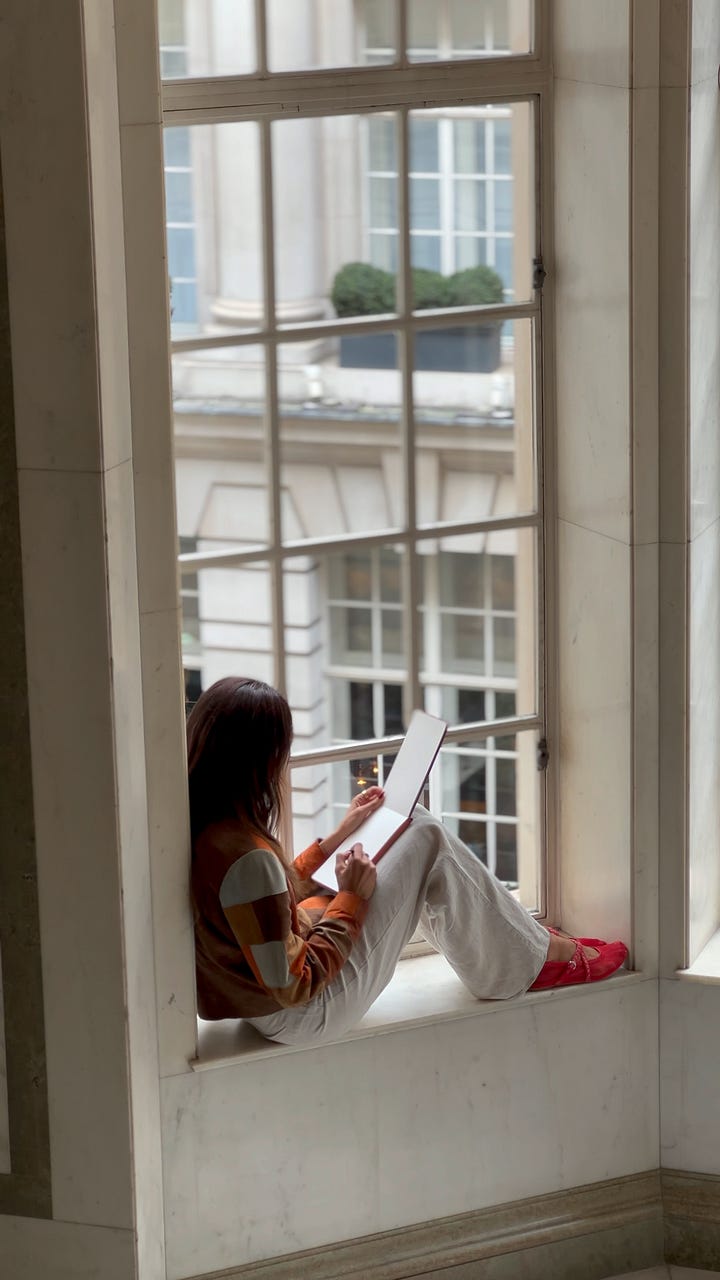

On a crisp autumn afternoon in London's notorious Rosewood Hotel, I found a hidden spot in a window ledge to nestle. Amid the cacophony of street performers and the rustle of golden leaves, I was captivated by the view and permitted myself to draw without looking for 5 minutes straight. My subject was the iconic courtyard of the Rosewood Hotel. I often do this exercise as a way of meditating. I like to be surprised by what is on the page afterwards, and this time, I liked what I saw. What struck me was not the accuracy of my rendering but rather its deliberate imprecision. Lines overlapped, perspectives skewed, and yet, paradoxically, the essence of the building seemed more present in this sketch than in the photographs I'd seen.

This encounter led me down a rabbit hole of artistic philosophy and cognitive science, exploring a question that has long intrigued artists and thinkers: Why do imperfect representations often feel more "real" than their polished counterparts?

Elaine Scarry states that our brains are constantly engaged in a process of "imagining." When we encounter incomplete or imperfect information, our minds instinctively fill in the gaps, creating a richer, more personalised experience. "It's not about what's there," Scarry explains, "but what isn't there that prompts our minds to engage more deeply."

My brain whirls… conjuring examples of when overlapping lines shouldn’t make sense, but they do—for example, people speaking over each other in conversation or layers of sound in a streetscape.

This concept finds resonance everywhere - think about theatre. Julie Taymor (director of “The Lion King” on Broadway) shared her thoughts on the power of suggestion in performance. “When everything is spelt out for the audience, it can become static, even lifeless," Taymor muses. “But give them room to imagine, and suddenly the performance becomes a collaboration between artist and viewer."

The idea extends beyond the realm of visual arts. In literature, Ernest Hemingway's iceberg theory* advocated for minimalist prose, suggesting that the strength of a story lies in what's left unsaid. In music, improvisationalist (GOAT) Miles Davis elevated the importance of the notes not played.

Our brains constantly make predictions about the world around us, using past experiences to fill in missing information. What we perceive is not the world as it is but our brain's best guess about what's out there. In this light, the imperfection of my humble little sketch became a playground for my controlling mind.

In other words, I liked it because it engaged me more deeply than a flawless representation ever could.

So, why do I write a newsletter about a sketchy sketch I surprisingly loved?

The celebration of imperfection is not just an artistic conceit; it reflects a fundamental truth about human perception and experience. In an age where digital perfection is at our fingertips, there's a growing appreciation for the handmade, the rough-hewn, and the authentically flawed. It's a reminder that our imperfections are essential to ENJOYING our humanity.

As I left my window spot that day, the sketch of the facade tucked carefully in my notebook, I couldn't help but see the city through new eyes. The crooked lines of fire escapes, the asymmetrical arrangement of windows, the haphazard traffic flow – all seemed to pulse with a vitality that perfect order could never capture. In embracing imperfection, we open ourselves to a richer, more nuanced understanding of the world around us and, perhaps, of ourselves.

Till next week,

Karimah Xoxo